It’s easy when the world is falling apart to feel like a tragedy is too big to look at, too dire to capture in words. It’s easy to think that nothing an artist does can possibly matter—you’re just one more small weak meat envelope against an unbeatable system. But of course this is exactly when you have to engage with the world. It’s an artist’s most important job: to look at the world you’d rather hide from, to engage with tragedy, to wring humor and joy out of wretchedness.

In 1988, Tony Kushner began writing a play called Angels in America: A Gay Fantasia on National Themes. It was supposed to be about two hours long, and he wanted it to be about gay men, the AIDS crisis, and Mormonism…and he knew there was an angel in it. He was also choosing to write about what was then the very recent past. The first version of the first half of the play (which ended up being over seven hours long) premiered on stage in London in 1990, and on Broadway in ’93. The play is set in 1985-6—not the neon tinted, shoulder-padded dream of American Psycho, or even the manic hedonism of The Wolf of Wall Street, but the desolate, terrifying time in New York when the queer community was fighting AIDS with little recognition from a conservative government, when racial progress was at a standstill, and the increased visibility of the women’s and queer rights movements were under constant attack by the Religious Right.

The easy thing would have been to turn away and write about a lighter topic, but Kushner looked at the attacks on his community and set out to write a play that would offer comfort, inspiration, and even hope to a generation of people.

I know that when I started TBR Stack part of the point was for me to read my way through books I hadn’t gotten to yet, and that is still my main MO.

BUT.

It’s pride month, and what I really wanted to talk about this time was Angels in America, because if I had to pick one reading experience that was IT, the one, the triple underlined, bright neon Book That Saved My Life? It’s this one.

First, a quick plot summary: Prior Walter and Louis Ironson are a gay couple living in New York. When Prior learns he has AIDS, Louis leaves him and embarks on a fling with a closeted Mormon named Joe Pitt. Joe’s depressed wife, Harper, self-medicates with Valium. Joe’s boss, Roy Cohn (yes, that Roy Cohn), pressures Joe to take a job in the Justice Department to act as his inside man after he learns people are trying to get him disbarred. Roy then learns that he, too, has AIDS. Belize, Prior’s best friend, is assigned as Roy’s nurse, and Joe’s mother, Hannah, flies out from Salt Lake City and ends up caring for both Harper and Prior after they’re abandoned by their partners. Also, there’s an Angel who won’t leave Prior alone, and the ghost of Ethel Rosenberg has decided to haunt Roy, and everyone is in a tremendous amount of pain both physical and psychological. Got all that?

The play gave me a window into the mythical land of New York, a quick education in queerness, socialism, and Mormonism, and an ice-water bath introduction to the early days of AIDS. No one had any explanations at first, or any overarching reason why dozens of men would suddenly get illnesses like Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia or Kaposi’s sarcoma, two common symptoms that had been incredibly rare until the early ’80s. The first patients were young, otherwise healthy men, most in New York, and the only throughline seemed to be that they were gay.

It also captures is the sheer panic that came with the early days of the AIDS epidemic, and the way it was immediately weaponized against the queer community. With the syndrome being called “gay cancer,” fundamentalist preachers were only too happy to call it a punishment from God; people were calling for quarantines of gay men; people were terrified that you could catch it from public restrooms. And William F. Buckley—a tweedy scholarly man considered the leading intellectual of the Right—said that people with AIDS should be tattooed both on the forearm (so needle-sharers would be alerted) and on the ass (so gay men would be alerted during sex). He suggested this seemingly in all seriousness, apparently not realizing that visibly tattooing people would put them at risk of being attacked, and seemingly also blind to the resemblance to the serial numbers tattooed onto the arms of people who had, two generations earlier, been rounded up and thrown into Holocaust Centers concentration camps.

There were several plays around the same time that tackled AIDS: Larry Kramer’s The Normal Heart (1985) and The Destiny of Me (1992); Paul Rudnick’s Jeffrey (1992); Terrence McNally’s Lips Together, Teeth Apart (1991) and Love! Valour! Compassion! (1994). Indie films Parting Glances (1986) and Longtime Companion (1990) focused on gay men in the early days of the virus. Shortly thereafter Philadelphia (1993) and Rent (1994) were much bigger budget, higher-profile productions that centered straight characters, while the prestige medical drama And the Band Played On (1993) focused on the epidemic. All of these were pure realism, with the ravages of the illness depicted just as starkly as political indifference and societal prejudice. (Parting Glances and Jeffrey each get a single dream sequence/angelic visitation involving a friend who has died of AIDS, but these are both anomalous moments explained away by grief.)

Angels could have been a realistic play, but Kushner instead chose to do something crazy. Something that should not have worked. He chose to reach beyond what realism could accomplish and infuse the play with fantastic elements, which were treated with just as much respect as the domestic drama and harrowing scenes of illness. Prior Walter begins having visions, but these may just be caused by his AIDS medication. Over in Brooklyn, Harper Pitt also has visions, but these may just be caused by the not-quite-suicidal doses of Valium she takes to get through the day. Prior and Harper meet up in dreams, but since those dreams are, as Harper says, “the very threshold of revelation”, the two are able to intuit real truth about each other. Prior goes to Heaven, and his actions there have real world consequences. Finally, Roy Cohn, the slightly-fictionalized villain based on the real-life (and pretty damn villainous) Cohn, is visited by the ghost of Ethel Rosenberg. But Roy is also suffering from AIDS and whacked out of his mind on pain meds, so, Ethel might be a hallucination, as well? Except then there’s a point when Ethel is kind enough to call an ambulance for Roy, and paramedics actually show up and take him to the hospital, so…where are the lines of reality drawn?

But by the end of the play Kushner chooses to go even further. He takes the complex philosophical idea of the Angel of History, makes her real, and hauls her down to Earth for a wrestle. And when she got away from him, he sent one of his characters to Heaven so he could confront her there.

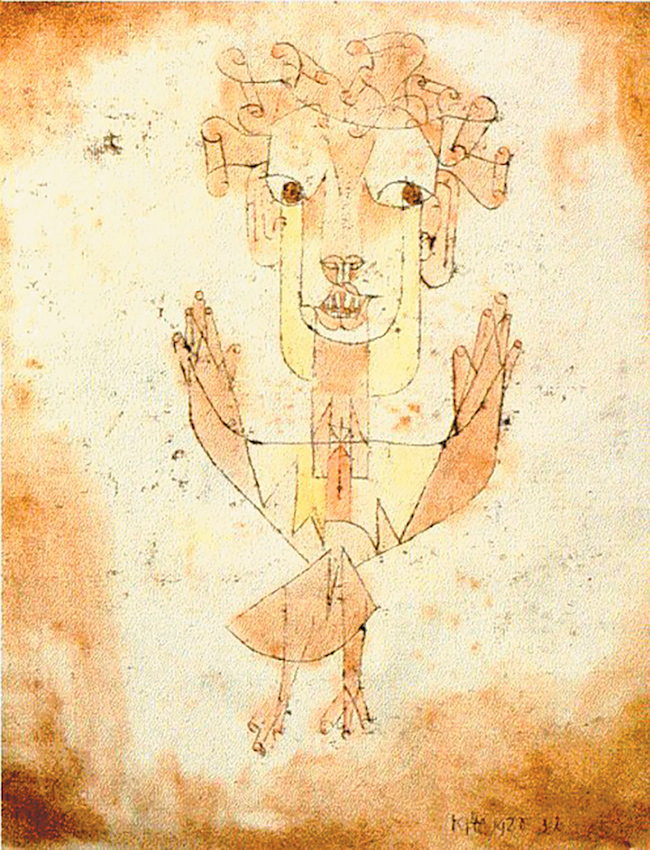

In 1920 Paul Klee painted a portrait of a creature he called Angelus Novus—New Angel. The following year a philosopher named Walter Benjamin bought the print, and became obsessed with it, eventually writing about it in his final paper, Theses on the Philosophy of History. You can read them here, and it’ll take about ten minutes to read the whole thing. Benjamin was dead about a month later—having fled Vichy France, he decided to kill himself in Spain so he wouldn’t be sent to a Holocaust Center death camp.

The Theses is a short work, twenty numbered paragraphs. In Paragraph Nine, Benjamin returns to his painting:

A Klee painting named Angelus Novus shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.

Kushner takes this Angelus Novus and gives it a voice, agency, a mission. He makes it one of Seven Continental Principalitiesan Angel for each continent, with America obviously snagging the one who has the most direct experience of progress.

Prior begins receiving visions from the Angel of America, and he clings to them because the beautiful voice of the angel not only comforts him, at one point he even says that it’s all that’s keeping him alive. Someone reading this or watching it from the vantage point of 1993 would probably think that the angel would offer a comforting message, some sort of hope, succor in the face of plague and death? But that’s not quite what happens.

At the climax of the first play she crashes through his ceiling, announcing herself. Prior is terrified, the play ends. (Apparently many viewers assumed that was the end, and that the angel had come through the ceiling to collect Prior, who had died alone after a series of hallucinations.) But in the second half of the play, Perestroika, Kushner subverts the saccharine late ‘80s-early-90s angel craze and turning it into a dark exploration of Jewish mysticism, Mormonism, and socialism. He recommits to the fantastic element and makes it a central part of the story. Prior journeys to Heaven and meets with a council of angels…but these are not the touchy-feely, benevolent creatures of CBS evening dramas, or the adorable cherubim cavorting with ceramic kittens on your favorite aunt’s fireplace mantle. These aren’t even the types of celestial beings you’d find atop a Christmas tree. These angels, each representing a different continent, are cantankerous, angry, ready to wrestle and fight humanity for their cause. They want history to STOP. They want humanity to STOP. Stop innovating, stop creating, stop breeding, stop progressing, just cut it out and give the universe some peace, because each new innovation wracks Heaven with earthquakes. The novelty of humans has driven God away, he’s abandoned his angels and his humans and taken a powder, who knows where. The message resonates with Prior, newly diagnosed with AIDS, feeling his young body collapse into terminal illness, and abandoned by his partner Louis—he fears the future. Any change can only be for the worse.

And yet. As Prior wrestles with the message, and discusses it with friends, he realizes more and more that to stop is to become inhuman. His help comes from two marvelously diverse points: his BFF Belize, a Black nurse who has done drag in the past but somewhat given it up as politically incorrect, and Hannah Pitt, the—say it with me now—conservative Mormon mother of Prior’s ex-partner’s new lover. Hannah, who turns out to be far more than a stereotype of religious fundamentalism, is the only one who believes in Prior’s angelic visitations. She instructs him on how to wrestle, literally with the angel, in order to gain its blessing. And so Prior and the Angel of America reenact the Genesis story of Jacob wrestling an unnamed angel/God (the event which led to Jacob renaming himself Israel, or “he who wrestles with God”) right there on the hospital room floor. Prior wins, and climbs a flaming ladder to Heaven, a beautiful derelict city. It doesn’t matter anymore if this is hallucination or reality: what matters is that Prior Walter, sick, lonely, human, is facing a council of Angels and rejecting their message. What matters is that the human is standing up to the awe-inspiring, fantastical Angel of History, and telling her that progress is not just inevitable, it is also the birthright of humanity.

In this way, by embracing fantasy, making History an Angel, and making that Angel a living, breathing, wrestle-able character, Kushner is able to grab Capital Letter Concepts like Plague, Progress, Socialism, Love, Race, and embody them. And since this play is about AIDS, those bodies are sick, suffering, tortured, covered in lesions and blood. The Angels themselves are in tatters, because Progress is a virus that’s killing them. The play only works because of its fantasy element—the fantasy allows Kushner to tie the AIDS crisis to other huge historical markers, and make straight people pay attention. It also means that the play will never be a dated nostalgia piece, because it’s about so many huge ideas that even if a cure for AIDS was found tomorrow Angels would remain vital. And maybe most of all it takes these characters who could have been trapped in a domestic tragedy, and it lifts them out of their own time and their own pain and posits them as the most important people in history. And after doing that, the play ends with Prior Walter, AIDS survivor, turning to the audience and blessing all of us. “You are fabulous creatures, each and every one. And I bless you: More Life. The Great Work Begins.” We are brought into the play, and into history, just as important as any Angel.

About that…Tony Kushner, a gay Jewish man living through the AIDS crisis of the 1980s, visiting loved ones in the hospital, attending funerals, all the while knowing that he might be the next one to get bad news, had every reason to despair. Instead he wrote a story of hard-won hope. Rather than maudlin angels swooping down to fix everything, he gave us flawed, fabulous humans, working together to form families. Rather than cower in fear of infection, he put men naked in bed together onstage. Rather than let the fortunate few who remained unaffected off the hook, he gave us Prior Walter shitting blood and screaming in agony. Rather than succumb to bigotry, he gave us a conservative religious woman who becomes the most three-dimensional character in the play. Rather than succumb to hate, he made his characters say the Kaddish over Roy Cohn.

None of us can see the future. We are all the Angel of History, pushed forward as life unfurls around us, helpless to stop time or change. But we can be present in the world and do whatever we can to help each other, support each other, keep each other safe. Kindle hope in the face of darkness.

Now. Now. Now. Now.

Leah Schnelbach knows that as soon as this TBR Stack is defeated, another will rise in its place. Come spread your wings, fabulous people, and give her reading suggestions on Twitter!